The University of Helsinki has started using epistemically opaque competency assessment tests sold by a private recruitment company in the application process for salaried PhD positions. This does not promote fairness, objectivity, or transparency. It also goes against the principles of responsible researcher evaluation.

The University of Helsinki has renewed its application process for salaried PhD positions. This change affects both the PhD students applying for over 100 paid four-year doctoral positions, and the ones applying for 236 three-year positions in the doctoral training pilot. (University of Helsinki, Flamma News 3.10.2024). The renewed process has an element that has raised concerns in the academic community. Each applicant must now complete a series of online competency assessment tests. One test is claimed to assess the personality of the applicant, while others are meant to evaluate verbal and mathematical skills.

The University of Helsinki purchases these tests from AON, an international company that develops and sells recruitment-related assessment services. The overall goal of the revised application process is to improve efficiency and to “ensure a fair and objective assessment of applicants in large numbers of applicants, as well as to ensure transparency and consistency in recruitment processes” (University of Helsinki, 2024, Flamma News 3.10.2024). We share the concerns of many in our community: the use of these tests does not promote fairness, objectivity, or transparency.

Psychometric tests in recruitment

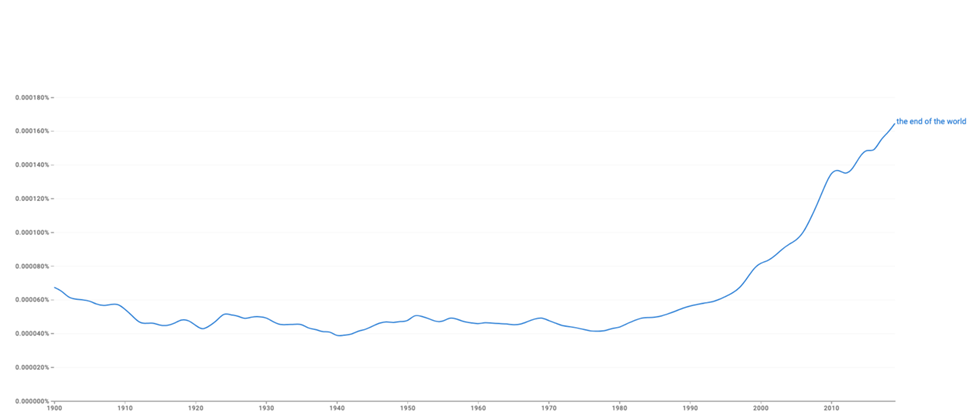

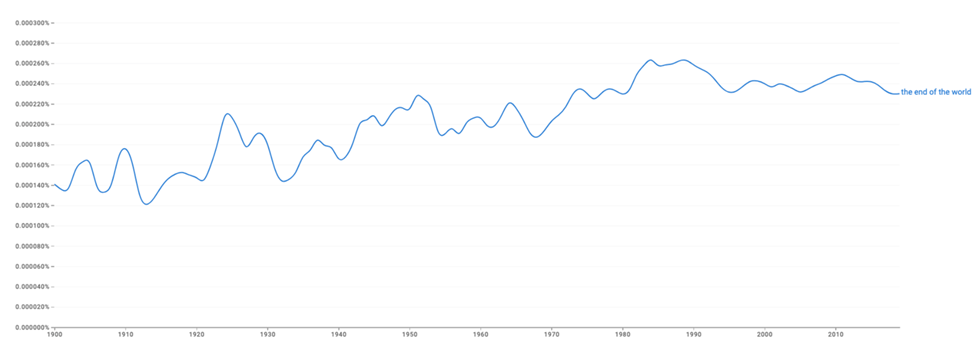

Psychometric testing has been a mainstream recruitment trend for decades (Searle & Al-Sharif, 2018). During the 20th century, psychometric testing was developed to meet the needs of educational institutions, the military, and companies recruiting employees. The guiding values in the development of psychometric testing have been objectivity, fairness, and utility (Wijsen et al., 2020).

Given the significance of psychometric testing in modern societies, it is unsurprising that the concepts of objectivity and fairness are cited as motivators for introducing psychometric assessments at the University of Helsinki. However, the doctoral school responsible for the new application process has not clearly defined what is meant by the “objective” and “fair” processes that are supposed to add to the “transparency” of the selection process. Our aim is to clarify these terms based on our previous and ongoing research. Unfortunately, this clarity does not alleviate the concerns raised by University of Helsinki researchers and students. On the contrary, shedding light on these concepts reveals central problems in the use of psychometric testing.

The concepts of objectivity and fairness in psychometric testing

In psychometric testing, “psychometric objectivity” (Seppälä & Małecka, 2024) refers to the aspiration to eliminate personal judgement from the assessment of personality and skills, ensuring that test results do not vary depending on the person conducting the measurement (Wijsen et al., 2020). This form of objectivity aligns with the notion of meritocratic fairness, which holds that the most qualified individuals should receive the greatest rewards (Wijsen et al., 2020) — in this case, the salaried PhD positions. In psychometrics, fairness has often been operationalized as developing methods to ensure that similar individuals are treated similarly (Wijsen et al., 2020).

However, meritocratic notions of objectivity and fairness have long been criticised for neglecting fairness of outcomes, particularly across demographic groups (Seppälä & Małecka, 2024). Socioeconomic backgrounds shape individuals’ skills and motivation, and these backgrounds are unequally distributed among groups. For example, parental academic background influences young adults’ higher education choices in Finland, although the effect is smaller than the OECD average (OECD, 2024). Therefore, meritocratically fair and objective procedures produce outcomes that sustain inequalities between groups (Au, 2016; Sandel, 2020). In other words, tests that strive for “psychometric objectivity” are inefficient tools if the aim is the fair treatment of demographic groups.

The use of such tests can also heighten discrimination against some groups. When “psychometric objectivity” is sought by using standardised tests with time limits, there is a significant risk of discriminating against many minorities, such as neurodivergent people. For instance, in the United States, the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation has recently appealed to the Federal Trade Commission, claiming that AON’s personnel assessment products discriminate against individuals based on disability, health status, and ethnic background. Regarding the ADEPT-15 test used by the University of Helsinki, the complaint states the following:

Algorithmically driven Adaptive Employee Personality Test (“ADEPT-15”) adversely impacts autistic people, otherwise neurodivergent people, and people with mental health disabilities such as depression and anxiety because it tests for characteristics that are close proxies of their disabilities – characteristics which are likely not necessary for essential job functions for most positions – and their disabilities are likely to significantly impact the scores they receive for those characteristics. (ACLU 2024.)

Competency assessment tests do not promote fairness

“Fair” methods may be “fairer” to some groups than others (Rios & Cohen, 2023), as they sustain inequalities between social groups, and may heighten discrimination against some groups. This does not sound fair. But how then should we understand fairness?

Luckily, the University of Helsinki is committed to a relatively clear characterisation of fairness. Fairness in researcher evaluation means, among other things, that “[c]haracteristics or circumstances associated with persons being evaluated or people close to them that are irrelevant to the objective of the evaluation must not be used as evaluation criteria.” (University of Helsinki: Responsible Evaluation of a Researcher.)

The use of a personality test in recruitment requires choosing a set of personality traits that are sought, and others that are not. We have tried to ask how these personality traits have been chosen in the case at hand, and whether AON took part in the choosing process, but so far have not received an answer.

There is an ongoing discussion about whether personality tests – even the best ones – are able to predict job performance (Zell & Lesick 2021). But we are not talking about typical jobs here: we are talking about academia. It is doubtful that there are any personality traits that would be beneficial in all academic fields. Nor does it seem plausible that there would be any personality traits that might not be useful in some academic field. And it is quite likely that there are academic fields where the personality traits of a researcher do not matter at all. Therefore, using a personality test in the application process for salaried PhD positions means using characteristics associated with persons being evaluated that are irrelevant to the objective of the evaluation. By the definition accepted by the University of Helsinki, this is unfair.

But even more worryingly, it is highly questionable whether any personality traits of an individual, or even their competencies, can be reliably recognised by the means of any kind of an online test without combining it with a personal interview with a trained professional such as a psychologist. The Finnish Psychological association (2019) strongly discourages against the use of any test results – either personality test results or competency test results – without such an interview, where the results are discussed and interpreted.

It is therefore reasonable to doubt the ability of AON’s tests to reliably measure what they claim to measure. If the tests are unreliable, they either bias against some applicants in ways unknown and unjustified, or are tantamount to tossing a coin. Neither option promotes fairness.

Competency assessment tests can decrease cognitive diversity

In addition to being unfair, the use of such tests may be epistemically harmful.There is ample evidence of the epistemic benefits of social and cognitive diversity in science (see Rolin, Koskinen, Kuorikoski & Reijula 2023).

The introduction of psychometric testing threatens diversity among PhD students and university staff. Because such tests sustain inequalities between social groups, their use does not increase social diversity in the academic community. And particularly the introduction of a personality test in the application process may decrease cognitive diversity in the selected group.

A group is cognitively diverse when its members differ, for instance, with respect to their expertise and skills, or problem-solving heuristics.

As noted above, the use of the ADEPT-15 personality test may discriminate against some groups, notably neurodivergent people. In general, the use of such a test in the application process for salaried PhD positions may mean discriminating against people whose problem solving strategies do not lead to “successful” performance in the alleged personality test. This is worrisome for two reasons: first, it is unfair, and, secondly, it is epistemically harmful.

Competency assessment tests do not promote objectivity

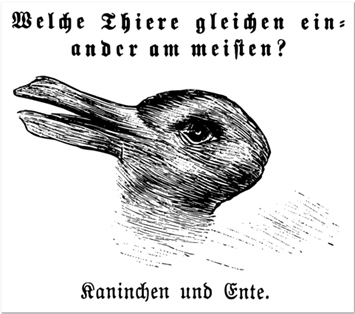

As mentioned above, “psychometric objectivity” refers to the attempt to eliminate personal judgement from the assessment of personality and skills. According to many critics, this just creates an illusion of objectivity, as the assessment methods sustain inequalities between social groups. In other words, they are biased against some groups – which gives reasons to question their objectivity.

Objectivity is a contested concept with multiple meanings. One of us has suggested a way to understand the relations between the different meanings of objectivity in science: When we call something objective, we claim that some important risk or risks of error to which we as human beings are prone has been effectively mitigated, and we can therefore rely on that something. For instance, we may call a research process objective because we have ensured that we can change the researcher in charge of the process, and the results stay the same. In other words, the subjective biases of an individual researcher do not bias the outcome (Koskinen 2020).

This idea can be applied here, even though we are talking about HR, not science. When people strive for “psychometric objectivity”, the very human risk that is being avoided is that the evaluators might be biased, and their personal judgements could therefore lead to suboptimal decisions. The suggested solution is to replace the evaluators’ judgement with test results. The critics we discussed above (Au, 2016; Wijsen et al., 2020) claim that focusing on individual biases is misleading. It is the inequalities ingrained in our societies and operating on multiple levels that are the really important problem: they lead to suboptimal decisions in recruitment, because some candidates never have a proper chance. Psychometric objectivity is toothless against this problem, as the tests do nothing to alleviate the systematic disadvantages of some demographic groups.

We agree. The problem is well illustrated by the fact that several companies currently offer training packages and courses promising better performance in AON’s tests. If they really work, then the applicants who have the resources to pay for the training fare better in the tests. In other words, the tests discriminate against the poorer candidates in a very familiar way, sustaining inequalities between social groups. Recruitment decisions based on the test results are therefore bound to be suboptimal.

The use of competency assessment tests can also decrease the objectivity of the selection process.The tests are introduced as a strategy for ensuring that the individual evaluators’ biases do not lead to suboptimal decisions in recruitment: the candidate is not chosen just because the evaluator, for instance, liked their charisma. However, there are many different kinds of risks of error that should be taken into account. In addition to the evaluators individual biases, systematic biases in the tests can lead to suboptimal decisions. It is not a good idea to replace the first type of bias with the latter (Koskinen 2023). If the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation is right, and AON’s tests really do systematically discriminate against individuals based on disability, health status, and ethnic background, then the use of the tests leads to suboptimal decisions with regard to individuals belonging to these groups. As a result, it may become even less likely than before that such individuals are recruited. If so, then the use of the tests has decreased the objectivity of the selection process.

To whom do “objective” and “fair” recruitment methods give power?

Another important question to ask when introducing psychometric methods is to whom power is transferred and from whom it is taken away (Kalluri, 2020; Seppälä & Małecka, 2024). At the University of Helsinki, the power dynamics are quite clear. The psychometric competency assessments diminish the importance of the scientific merits of the PhD plans in selecting PhD students for salaried positions. This means that the decision-making power is transferred to AON and AON-certified personnel in the university’s HR department. This means that the academic community’s power to choose its new members is reduced.

There could perhaps be arguments for this shift in power if AON and the HR department could demonstrate

1) that the personality and skills assessments are grounded in the best theories of personality and organisational psychology, and

2) that the test results have sufficient predictive power for successfully conducting PhD research in all academic fields.

We have already expressed some doubts about the second point. It seems unlikely that any competence test or personality test could produce results that would be relevant in all academic fields. The University of Helsinki is committed to the national recommendation of researcher evaluation, according to which “evaluation must take into account the diversity of research and outputs” (University of Helsinki: Responsible Evaluation of a Researcher), so this is problematic. Moreover, we have seen no independent evidence of AONs tests’ predictive power in any contexts, let alone academic ones.

As to the first point, AON, of course, claims that high scientific standards have been met. According to AON (2024), “Aon’s solutions strengthen hiring through psychometric assessments that are backed by science.” In other words, the assessments are “[r]eliable, robust, and research-based psychometric assessments.” But are AON’s claims justified, and how can we verify them?

This takes us to our biggest concern: how can we secure the transparency of a recruitment process if we use tests that are not transparent?

Epistemically opaque competency assessment tests do not promote transparency

AON’s tests, like all similar tests developed by commercial enterprises, are protected as business secrets. The companies typically claim that the tests are valid, reliable, robust, “research-based”, “backed by science”, and so on, and have marketing materials that support these claims. However, these tests are not independently validated. They do not compare to the kind of genuine psychometric tests that are used in clinical work and that have gone through an academic process of test development and validation. To put it simply, psychometric tests developed by commercial enterprises are not peer-reviewed, and independent replication studies seldom happen – and when they do happen, the results might not be flattering to the firms (Rhea et al. 2022).

Because the tests are protected as business secrets, they are epistemically opaque black boxes both to the applicants who must take the tests and to the employers who use such services – in this case, the University of Helsinki. So it is not possible to assess how they work, and to what degree they are perhaps based on psychological research. Based on AON’s website, it is, for instance, not possible to tell even the psychological theory of personality that the company uses in their personality test – if any. The ADAPT-15 test – which the University of Helsinki now uses – seems to include six “broad work styles” and fifteen “aspects of personality” (AON, 2022; AON, 2024), so at least it appears that it is not based on Big Five, the best-known and widely accepted psychological model of personality (Zell & Lesick 2021; see also Forsell & Koskinen unpublished manuscript).

The same problem of epistemic opacity applies to all of AONs tests that the University of Helsinki (Flamma News, 3.10.2024) now uses: we know nothing about the alleged research on which “the scales lst, scales clx, and scales numerical & verbal tests” are based. Because there are no independent studies that would confirm that the tests do what they are claimed to do, and because we have no access to the tests, it is impossible to assess their epistemic value. We have no idea whether they do what AON’s marketing materials claim they do, and there is no independent evidence of their predictive power.

This is against the principle of transparency as it is characterised in the general principles of responsible researcher evaluation, to which the University of Helsinki is committed. Transparency, according to these principles, means that the “objectives, methods, materials and interpretation of the results must be known to everyone” (University of Helsinki: Responsible Evaluation of a Researcher).

The University of Helsinki should not use epistemically opaque tests in recruitment

The University of Helsinki is committed to the national recommendation of researcher evaluation (University of Helsinki: Responsible Evaluation of a Researcher). The general principles of this recommendation are transparency, integrity, fairness, competence, and diversity. We have just argued that the use of epistemically opaque, not independently validated psychometric competency tests in recruitment goes against the principles of fairness, diversity, and transparency. Competency remains an open question, as due to trade secrecy, we cannot evaluate it.

“Integrity” on this list of principles is specified to mean that “the evaluation must be conducted in accordance with practices recognized by the research community”. Using epistemically opaque “black box” tests that have not been independently validated – using them for any purpose – is against basic practices that are recognised across all academic fields. Members of our community are now being selected in ways that go against some of the most elementary established practices in academia. The University of Helsinki should never use such tests in recruitment.

Inkeri Koskinen is an Academy Research Fellow in Practical Philosophy and the president of the National Committee of Philosophy of Science. In her project Objectivity in Contexts she studies the notion and the normative ideal of objectivity. She is also the PI of the Aaltonen foundation project Pseudoscience in Finnish Work Life.

Päivi Seppälä is a doctoral researcher in the Doctoral Programme in Philosophy, Arts, and Society at the University of Helsinki. She is a member of the research team of the Aaltonen foundation project Pseudoscience in Finnish Work Life. She is also a STOry-certified professional supervisor and has a 10-year work experience in financial administration and HR. Her PhD research focuses on recruitment technologies, discrimination in recruitment, and pseudotechnologies, and is currently funded by the Kone Foundation.

References

ACLU complaint to the FTC regarding Aon Consulting, Inc. May 30, 2024. https://www.aclu.org/documents/aclu-complaint-to-the-ftc-regarding-aon-consulting-inc Accessed 17.10.2024.

AON (2022). ADEPT-15: Adaptive Employee Personality Test. https://www.aonhumancapital.co.in/home/for-employers/assessment-solutions/leadership-assessments/adept . Accessed 15.10.2024.

AON (2024). Pre-Hire Talent Assessment.

https://www.aon.com/en/capabilities/talent-and-rewards/pre-hire-talent-assessment . Accessed 10.10.2024.

Au, W. (2016). Meritocracy 2.0. Educational Policy 30, pp. 39–62.

Finnish Psychological Association, Henkilöarvioinnin sertifiointilautakunta (2019). Henkilöarviointi työelämässä: ohjeistus hyviksi käytännöiksi. 4.9.2019. https://www.psyli.fi/psykologin-tyo-ja-koulutus/patevyydet-ja-sertifikaatit/henkiloarvioinnin-sertifikaatti/ . Accessed 15.10.2024

Forsell, M & Koskinen, I. Unpublished manuscript. Commercialisation, Opacity, and Demarcation: The Use of Personality Tests in Recruitment.

Kalluri, P (2020). Don’t ask if artificial intelligence is good or fair, ask how it shifts power. Nature 583, pp. 169–169.

Koskinen, I (2020). Defending a risk account of scientific objectivity. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 71:4, pp. 1187–1207.

Koskinen, I (2023). Participation and Objectivity. Philosophy of Science 90(2), pp. 413-432.

OECD (2024). Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/c00cad36-en. Accessed 10.10.2024.

Rhea, A. K. et al (2022). An external stability audit framework to test the validity of personality prediction in AI hiring. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 36, pp. 2153–2193.

Rios, K. & Cohen, A. B (2023). Taking a “multiple forms” approach to diversity: An introduction, policy implications, and legal recommendations. Social Issues Policy Review 17, pp. 104–130.

Rolin, K., Koskinen, I., Kuorikoski, J., Reijula, S. (2023) Social and cognitive diversity in science: introduction. Synthese 202, 36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04261-9

Sandel, M. (2020). The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good? Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Searle, R. H. & Al-Sharif, R. (2018). Recruitment and Selection. in Human Resource Management – a critical approach, eds. Collings, D. G., Wood, G. T. & Szamosi, L. T. Routledge, pp. 215–237.

Seppälä, P. & Małecka, M (2024). AI and discriminative decisions in recruitment: Challenging the core assumptions. Big Data and Society 11(1).

University of Helsinki: Responsible Evaluation of a Researcher. https://www.helsinki.fi/en/research/research-integrity/responsible-evaluation-researcher Accessed 17.10.2024.

University of Helsinki (2024). The competency assessment used in the application process for doctoral researchers raises questions – the Doctoral School answers. In University of Helsinki News, Flamma, 3.10.2024. https://flamma.helsinki.fi/en/group/ajankohtaista/news/-/uutinen/vaitoskirjatutkijoiden-haussa-kaytetty-kyvykkyysarviointi-herattaa-kysymyksia-tutkijakoulu-vastaa/38547657 (login requires University of Helsinki user account).

Wijsen, L. D., Borsboom, D. & Alexandrova, A. (2021). Values in Psychometrics. Perspectives on Psychological Science 17(3). doi:10.1177/17456916211014183.

Zell, E. & Lesick, T. L. (2022). Big five personality traits and performance: A quantitative synthesis of 50+ meta‐analyses. Journal of Personality 90, pp. 559–573.